I was in DC for a day on 5 March to run a workshop for the World Bank on how to develop “smart cities”.

“Smart cities” is honestly a buzzword and when I get invited to speak, most people expect me to start with cool tech like AR, VR, AI, modeling and simulation, blockchain and the like.

The fact is that cities are complex ecosystems with very established ways of operating. If we want to disrupt them with technology in a way that benefits the masses (i.e. not just the upper middle class), we need dedicated work from the ground-up, coupled with political commitment. The aim is really to create a movement with many champions, not just a few bright sparks which fizzle out shortly.

If anyone is thinking of starting your smart city efforts, here are five tips I have, borne through many conversations and projects with smart city leaders worldwide.

-

Carve out space for ground-up innovation

When I first joined the public service, tech was really a downstream IT function, the proprietary territory of geeks. The realm of digital possibilities was beyond my imagination: I’d go about making policies, never thinking twice about the inefficiency of the data request and management process. It was just the ways things were done.

In 2014, a small group sprung up which touted new techniques for managing and analyzing data. They were eager to show us new things we could do with our data that we never imagined – natural language processing, k-means clustering, fancy visualizations. We didn’t have to wait 3 months and pay money to get data-sets; these should be available in real-time so we can make decisions on the go.

They made data science accessible. They were happy to experiment with small and large datasets, amorphous and specific problems. The more we worked together, the more I wanted to learn about these new techniques.

Technology, in the form of data science, became a way for me to solve the problems I cared about, such as the allocation of preschool places. It inspired me to take courses in R and Tableau (visualization) and apply these in my day-to-day work.

On reflection, it was so important that the small group of data scientists, user experience designers and machine learning scientists did not just stay in their box. They saw their role as tech evangelists, spreading enthusiasm and skills to the rest of us. They started a ground-up movement to make data science part of our work, and succeeded.

-

Build your core of “tech commandos”*

*term first used by my colleagues Daniel and Chi Ling here.

This is why, when people ask me what should be the first step in building a smart city, I never fail to raise the issue of building internal capabilities in the Government. In Singapore, we did not start with a large group of data scientists and software programmers. It was a small group of “tech commandos” who went about demonstrating value to the rest of the organization, before scaling up.

From my observations, three traits are important in picking “tech commandos”.

- First, credibility with the organization (an outsider trying to shake things up often results in an allergic reaction);

- Second, a strong HR instinct and the ability to assemble cross-functional teams – this does not mean that he/she must be the best technical executer;

- Finally, the commitment to the organization’s long-term capabilities (not just his/her own shining). This does not mean that the person has to be an internal hire. However, there must be a personality fit – we had one “tech commando” who had no public sector experience, but an infectious, humble energy that won people over.

These “tech commandos” are effectively the bridge between the bureaucracy and the budding team of experts. They must be allowed to organize their teams, build a completely different culture as they wish, and buffer their team from the bureaucracy. To deliver early value, they must have high-level backers who are intent on opening up use cases and data for them to demonstrate their skills.

Nurturing a small core of “tech commandos” is always one of the first steps a city needs to take when it aims for digital transformation. Implementing projects is one benefit. Beyond this, their technical expertise is critical in assessing procurement decisions, such as the trade-offs between “building or buying” products and solutions. Great talent delivering social impact also attracts more talent, and so the cycle begins.

-

Integrate across agency boundaries so that you truly transform the citizen experience

If cities want to radically transform the living experience of their citizens using technology, integration across digital services is often necessary. This necessitates some form of central planning – you cannot have different agencies building their own systems and creating multiple, disconnected touchpoints with citizens.

A great example of a developing country that managed to achieve this is India, with its “JAM Trinity”.

- –“J” for Jan Dhan, a free bank account for every citizen;

- “A” for Aadhar, a biometrically verified Digital Identity for every citizen;

- “M” for mobile, a mobile phone for every citizen.

- For every individual, these three are linked. Hence, on your mobile phone, you can verify your identity and make a bank transfer.

The integration across identity-bank account-mobile is what explains widespread adoption of these technologies in India. “Aadhar” the digital identity, was first launched in 2009. However, take-up rate only spiked in 2014, when the Government linked digital identities to bank accounts, and used that to directly transfer subsidies and provide free insurance to people.

Simply put, people start adopting a new way of living life when they see the value and benefit of doing so. In the digital world, integration is necessary.

In my presentation at the World Bank, I laid out five elements of a nationwide technology project, gleaned from lessons across developing and developed countries.* <this section is partially attributable to my colleague Kevin Goh and Tan Chee Hau, who visited India to study the Digital ID system closely>

- First, an ambitious, compelling goal. Modi himself championed the JAM trinity as the solution to financial, and hence social and economic exclusion if the poor. With a bank account, ID and mobile, everyone could connect to the formal economy and receive subsidies directly from Government. Almost S$20B of savings was to be yielded by solving tax evasion and the leaky pipe of subsidies due to inefficiency and corruption.

- Second, a clear operational strategy. Ask any Indian official and citizen, and they simply understand that “JAM” represents digital transformation. The Government went for end-to-end integration of these components. The huge amount of savings generated from “JAM” justified distributing free services and a massive communications campaign.

- Third, a clear governance structure. India designated agencies to set architectural standards for each of their digital identity and payments platforms. Setting standards ensures integration between components of a big system. In Singapore, we enforce standards not just by rules, but also by baking them into our platforms. For example, if developers use our NECTAR platform, they automatically comply with Government standards for development on the cloud, and other engineering best practices.

- Fourth, an open ecosystem. One of the most amazing things India did was to create an open, interoperable India Stack to support “JAM”, The India stack consists of API-based platforms which the private sector can build applications upon. For example, if you are a start-up wanting to build a microfinance solution, you can build on their existing architecture for digital identity and mobile payments. You do not need to start from scratch.

- Fifth, a massive focus on inclusiveness. When India went about getting every citizen to have JAM, they tried all means of reaching the unbanked: branch banking, mobile banking, online banking – you name it, they had it. They went on a massive campaign to reach the very last mile.

These are the five elements of any successful nation-wide technology project, which truly transforms the lives of citizens.

-

Setting the stage for public and private collaborations

When we talk about nationwide technology projects, does it mean that the Government has to execute on everything? By no means: some of the most cutting-edge innovation will always come from industry.

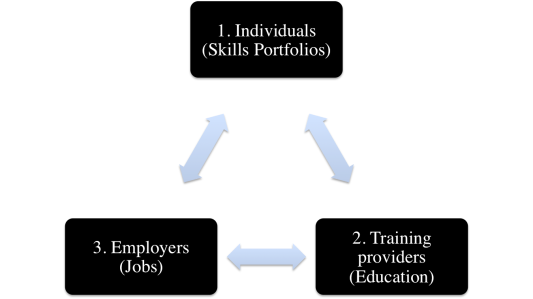

However, in developing smart cities, a new paradigm for the Government-private sector relationship is needed. Where in the past a Government simply procures digital infrastructure, products and service from the private sector (an out-sourcing model), what is needed now is more co-creation of possibilities and pilots between the public and private sectors, before deciding what to scale. The rapidly changing nature of technology means we are not quite certain which solution will work at the outset.

In working with private companies, Governments also need to lay out their expectations of an open ecosystem which enables maximal industry participation. This means that centralized platforms must have an open architecture and clear standards for interoperability, enabling other players can build applications upon it. Such a requirement runs against a traditional instinct for large companies to provide “closed ecosystems” which exclude all but those who use their proprietary operating systems.

Governments, start-ups and large corporates looking to build smart cities need to envision a new type of relationship, and build more platforms where trust and co-creation can be established. Some good examples include the Start-up in Residence Program, successfully run by the city of SF, and the Accreditation and Innoleap Programs run by the Singapore Government.

-

The advantages of developing countries in digital transformation

Friends from developing countries often tell me that “what Singapore does we’ll never be able to do”. They are surprised when I tell them that Singapore actually studies the smart city efforts of “developing” countries extremely closely.

Why has India raced ahead with their JAM trinity? Why does China light the path in e-payment adoption, while the U.S. and Singapore lag behind? Why was Estonia the first to develop a cutting-edge digital identity solution in the 1990s?

Users from developing countries can often more clearly see the value proposition of adopting the new digital solution. In contrast, people living in developed countries are typically wedded to the way things have always been done, such as using proprietary data centers instead of the cloud, paying with credit cards instead of e-payments, and using wired telephones instead of mobile. China is rapidly becoming the next innovation powerhouse because their people are cloud and mobile natives.

The lack of digital baggage is also a huge advantage. Estonia was able to leapfrog to the world’s most cutting-edge digital identity system because when they left Russia in the 1990s, they had zero legacy infrastructure to deal with. Just ask Taavi Kotkar, the ex CIO of Estonia, who told me a few years ago that he had to teach his kids what a “queue” was when he first took them on holiday outside Estonia.

Closing thoughts

“What in the world is a smart nation?” ask many of my (non-technical) friends when I first joined this team in the Government. Ultimately, people need to see, touch and feel how technology transforms their life in order to understand why it truly matters. If not, it remains in the realm of “esoteric”.

Building a smart city is ultimately about creating momentum throughout society to deploy tech for public good, not announcing a few superstar projects that fizzle out without momentum. I hope these five tips helped you think about what you need to do to build your own smart city which benefits the most people possible.