Job displacement is not new, but the scale and speed will increase in the coming years – a 2013 study by Frey and Osborne suggested that 47% of workers in America held jobs with a high risk of potential automation.

A few months ago, I wrote “Tackling AI-Driven Job Displacement: A Primer”, which argued that current avenues for people to retrain and find new jobs appeal mainly to those who are already motivated. When changing jobs is a choice, we don’t have a problem. However, when changing jobs is a necessity – which it will be as the speed of job displacement increases – we need the whole population to be motivated and proactive about re-skilling and finding new jobs.

How can we achieve this? For countries, this will be one of the defining challenges of our generation. If we cannot get a large proportion of our population to continuously re-skill to fit emerging jobs, we will face economic slowdown, increasing unemployment and most probably political upheaval.

In this article, I give a big picture of my ideal future, some of the outstanding efforts by tech companies and Governments, and the two big challenges that require collaboration.

My Ideal Future: The Big Picture

The job market today is wrought with inefficiencies which create barriers for job-seekers and employers.

- For individuals, the job search is intimidating because most of us do not have a good understanding of our skills, and how these map onto other jobs. There is also little incentive to obtain new skills if the link between these skills and future employment seems tenuous. It is a simple cost-benefit analysis.

- Employers are similarly in the dark. They can pay exorbitantly for skills that seem to be in limited supply when they unaware of people with adjacent skill-sets who could easily fill those roles with some investment in training. According to the Manpower Group, 46% of US employers reported that they had difficulty filling jobs.

- Education providers can profit greatly from the lack of transparency, when people are willing to pay for credentials that have no bearing on employment outcomes. On the other hand, they may struggle to reach a wider audience because only motivated people are seeking out their services. Adult education providers suffer here.

Imagine a different future with me for a few seconds.

If you are a regular person who wants to stay employed

Imagine a day when making plans for your next job is as much a part of your life as making plans for your next purchase: the barriers to your job search are so low.

- Just as you have a bank account, you have a skills account which elucidates all the skills you have accumulated through your education and previous jobs. These include self-reported skills, as well as skills that are verified by an authority that has studied the relationship between job descriptions and skills across sectors.

- Just as Facebook and Google push you advertisements based on your click history, you are consistently notified about emerging jobs with a close skills match to your account. “Good morning, we noticed that these jobs, which match your skillset, are trending. Salaries in these jobs are 5% higher than your current salary”.

- Suppose these jobs are sorted by degree of match to your existing skillset – 90%, 80%, 70%. You click on one and get an assessment of the best next steps – “Hi Karen, looks like you’re an 80% match to this job, and people with your profile have successfully entered this job by [taking this course] [doing a side project in this area] [taking a 1-month internship with X company]. Click to proceed”.

- You are also notified if your job is at risk, and nudged to take action. “Based on trends, your ‘risk modelling’ skill is increasingly automated by companies. Job listings for this are are decreasing at a rate of 5% a year and this is expected to speed up. Here are some adjacent skills you should pick up ASAP.”

When it’s so easy, won’t more people start to inculcate this as part of their lifestyle?

If you are an employer

Now imagine you are an employer. You need the right talent to serve emerging needs and want to access this talent, fast. Imagine if you not only had access to candidates who applied for their jobs, but candidates who had a >80% match to needed skill-sets, and could be a perfect fit if they underwent prescribed training or certification. You could reach out to these individuals and nudge them towards this, or sponsor training where it makes economic sense.

Rather than firing staff when functions are automated, you may prefer to move them into emerging jobs within the company, as long as the cost is not prohibitive. What if you could assess the degree of match between a potential lay-off with all the emerging jobs in your organization? This could help you make a choice on whether to invest to train the potential lay-off for these roles, or to favour of a new hire.

The information and incentives are better aligned to help you invest in training, rather than to go through rapid cycles of hiring and firing, which could undermine the fabric of your company.

If you are an education or training provider

Now imagine you are an education or training provider. When your courses are not standalone units but part of a pathway that quantifiably increases someone’s chances at securing an emerging job, your user base will likely increase. With more employers investing in education and skills training, your revenue also increases.

If you are a country Government

Now imagine you are a country government who has realized that the traditional model of centralized labour force planning is far too slow for the rate of job displacement. You can breathe easy because there is no longer a need for this outdated method. Individuals are motivated to reskill by good information and clear outcomes. Employers are willing to invest in training that will bring them the skills they need. Training providers fill real gaps and less people are overspending on education that yields little outcomes. The market is finally working – not just for the motivated few, but for your whole population.

Existing Efforts by Tech Companies are Laudable, but Insufficient

What I have laid out is pretty ambitious. It requires:

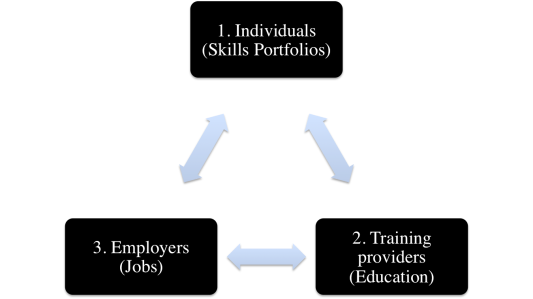

- A closed loop between individuals, training providers and employers (graph below). Having a common language to describe skills and jobs lies at the core – if we continue to describe the same skills and jobs in different words, employers do not know the full extent of their candidate pool, job-seekers do not know where they fit, and educational institutions do not know how their programs really help. It’s the wild, wild west.

- User-centric design that caters for the full range of our population: from the highly-motivated time-rich youth, to time-strapped parents and people who have worked in the same industry for decades. Some may not even use the internet. Employers similarly have to come on board – from the large multinationals to our mom and pop shops.

Several companies have already been working on parts of this puzzle. For example:

Google for Jobs, announced in June this year, leverages its powerful search engine to pull jobs which are most relevant to job searchers. To achieve this, Google’s powerful machine-learning model normalizes jobs and skills which are described very differently by employers and users. For example, if you search for “collections call centre job”, google will be able to flag out all the jobs that you will likely be interested in, even those that include none of your search terms, e.g. “Revenue Management and Care Representative.”

In my opinion, no one is better placed than Google to do this because of their experience with relational models, which group relevant search terms and results. Relational models form the fundamental basis for how Google yields relevant results even when you are not sure how to search for it. I wrote about how Google uses relational models in health search here, which has strong parallels to the job search.

Linkedin is well-positioned to create a closed loop between job-seekers, training providers and employers because all these players are in their platform. Linkedin helps individuals develop their skills portfolios through self-reporting and endorsements. It is also starting to map individual skills and jobs. If you have a premium subscription, you can see how your skills compare to other candidates and the percentile of applicants you fall into based on your Linkedin profile (example below). With the acquisition of Lynda.com, Linkedin is increasingly able to recommend courses to help people up-skill towards their desired job outcomes. To provide greater transparency to job seekers and employers, Linkedin’s Economic Graph team is also mapping the demand and supply of various skills across the world. However, Linkedin’s current business model is expensive for users, which could exclude a large part of the population and limit the data it collects.

Start-ups are also playing important roles in this ecosystem. Just two examples:

- Interviewed, an SF-based start-up, helps to close the loop between skills training and jobs. It started out by successfully developing a range of assessments to help employers assess the skills of candidates. It has since developed platforms such as Rightskill, where employers commit to hiring or at least interviewing people who obtain a certain score on hosted course. MooCs like Udacity have also made strides to closely link skills training to job placements – an essential move if they want to motivate a wider population.

- JobKred, a Singapore-based start-up, uses predictive analytics and data science to connect job seekers to their best opportunities, recommend personalised learning plans, and help employers zero in on their top prospects. They provide a customised user experience in the job search, making the job search less frightening.

Two Big Challenges Ahead

The creativity and experience of these companies will go a long way to achieving my ideal future. However, there are two big challenges ahead that I hope companies, Governments and non-profits will tackle together.

First, aligning the way that everyone describes skills.

Google has made leaps in working out the objective relationship between skills and jobs on the back-end. Their relational model is based on proprietary occupational and skills ontologies that they built in-house.

- Google’s occupational ontology gives a top-down understanding of 1,100 job families, a task typically undertaken by Governments.

- Google’s skills ontology maps out 50,000 hard and soft skills and the relationships between these skills.

- The skills and jobs ontologies are then mapped onto each other to paint an objective picture of the hard and soft skills required in each job, regardless of how they are described.

This is an amazing first step – let’s just take a moment to appreciate it. The fact that they make their relational models available through the Google Cloud Jobs API is even more amazing.

However, I believe these ontologies should not be kept on the back-end, used only when someone conducts an internet search for jobs. Many aspects of the job and education journey take place offline. Constraining the benefits to people who make proactive internet searches may miss out on a huge swathe of potential job-seekers.

Public and non-profit organizations should help with nudging individuals, employers and training institutions towards describing skills and jobs in the same language – perhaps Google can consider working with Linkedin, to combine Google’s job and skills ontologies with Linkedin’s data on self-reported skills, and make these a shared resource. However, the business model must make sense for the companies. Instead of users, Governments, charities or philanthropists should pay as this is a public good.

To reach the widest population, we also need to proactively help individuals populate and manage their skills accounts, just as they manage their bank accounts. UX designers need to work on interfaces that give people a bias to action. I covered some ideas in my “ideal future” section.

Second, bringing users on at scale to enable powerful Artificial Intelligence.

AI will play a huge role in enabling my ideal future: it underpins recommender systems and relational models, just to name a few areas. In turn, these AI-powered systems are enabled by data. Here we face a chicken-and-egg issue: unless we bring on the wider population to use the system, the software will not be able to serve the wider population. To collect data, we need to bring employers, individuals and educational institutions onto this system at scale.

This is an area where technology companies will benefit from the help of public and non-profit institutions. Singapore’s decision to give every citizen $500 for skills training and to create a unified skills and jobs database for individuals is a first step towards bringing a larger segment of the population on board. For segments of the population who are not digitally savvy, we need humans to come alongside and help them get onto the system.

Final thoughts

My ideal future is one where everyone – not just the highly motivated, time-rich or digital savvy – is empowered to continually update their skills and move to emerging jobs, rather than get left behind in the wave of job displacement. Finding your next job must be made as easy as finding the next place you want to eat at.

In all likelihood, this vision will not come through 100%. New safety nets must be put in place for people who simply cannot find new jobs. However, I believe that keeping people in jobs must be our utmost priority: not only are jobs the best safety net, there is also something dignifying about work that I do not believe can be replaced by a handout.

The goal of motivating a population at scale and overcoming inefficiencies in the job market is an area ripe for solutions by technology companies. I am encouraged that many – from conglomerates to start-ups – are working hard to achieve this vision. At the same time, I want see more collaborations that will enable large segments of our population to benefit. I would love to hear your thoughts – what would you like to see in this space?